Moral Policing vs Moral Leadership

By Dr. Sashi Sekhar Samanta

In every society, morality is a shared concern. It shapes behaviour, social norms, and collective conscience. Yet the way morality is enforced—or claimed—often reveals more about power than about ethics. In recent years, a troubling pattern has emerged in public life: the rise of moral policing in place of moral leadership. The difference between the two is not merely semantic; it defines the health of a democracy.

Moral policing thrives on control. It dictates how people should dress, eat, speak, love, and live, often enforced through intimidation, public shaming, or selective outrage. It targets individuals rather than systems, personal choices rather than structural injustice. Most dangerously, it claims moral authority without moral responsibility. Those who police morality rarely submit themselves to the same scrutiny they impose on others.

Moral leadership, by contrast, is rooted in example, not coercion. It does not shout instructions from a position of power; it demonstrates values through conduct. A moral leader does not ask, “Are you obeying the rules I set?” but rather, “Am I living by the principles I expect from others?” Leadership appeals to conscience, not fear.

The popularity of moral policing reflects an erosion of trust in institutions and leadership. When governance fails to deliver justice, equality, and security, morality becomes a convenient distraction. Policing personal behaviour is easier than addressing corruption, unemployment, gender violence, or environmental degradation. It creates the illusion of order while deeper disorder remains untouched.

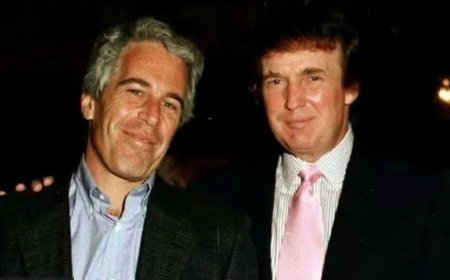

Selective morality is another hallmark of policing. Certain acts are condemned loudly, while others—often involving the powerful—are ignored or justified. This inconsistency strips morality of credibility. Ethics cannot survive double standards. When rules change depending on who is being judged, morality becomes a tool of dominance rather than a guide for living.

Moral leadership also understands the difference between law, culture, and conscience. Not everything that is socially disapproved requires state or vigilante intervention. A mature society allows space for diversity, dissent, and personal autonomy. Leadership recognises that moral growth is fostered through dialogue, education, and empathy—not force.

There is also a gendered dimension to moral policing. Women’s bodies, choices, and freedoms are disproportionately monitored and regulated, often in the name of culture or tradition. This reflects insecurity, not morality. A society confident in its values does not need to cage half its population to preserve them.

True moral leadership is uncomfortable. It requires standing against injustice even when it is popular, speaking truth to power, and accepting accountability. It demands consistency between public speech and private conduct. Most importantly, it focuses on systemic ethics—fair governance, social justice, and institutional integrity—rather than symbolic virtue.

In times of rapid social change, the temptation to police morality will persist. But history shows that societies progress not through enforced obedience, but through principled leadership. Morality imposed breeds resentment; morality practiced inspires trust.

The choice before us is clear. We can continue down the path of moral policing—loud, punitive, and hollow—or we can demand moral leadership—quiet, consistent, and transformative. One fractures society; the other strengthens it.

In the end, morality is not about controlling others. It is about governing oneself, responsibly and honestly. And that is where true leadership begins.