The Ashrama Dharma in Crisis: When Grihastha Begins at Sixty-Five

In the traditional Hindu way of life, human existence is divided into four ashramas, or stages: Brahmacharya (the stage of student life), Grihastha (the householder stage), Vanaprastha (retirement and withdrawal), and Sannyasa (renunciation and spiritual liberation). These stages are not arbitrary but deeply philosophical, offering a structure to ensure individual growth, societal harmony, and spiritual progress. However, when these stages are misunderstood or misapplied — such as when individuals begin the Grihastha stage in their sixties — the ripple effects are not only personal but civilizational.

The Inversion of Natural Order

Traditionally, the Grihastha Ashrama was meant to begin after proper education and character formation during Brahmacharya, typically culminating by the mid-20s. At this point, one is biologically, mentally, and socially primed to marry, raise children, contribute economically, and uphold dharma (righteousness). However, in recent times, a disturbing trend has emerged — individuals entering married life at ages traditionally reserved for Vanaprastha or even Sannyasa.

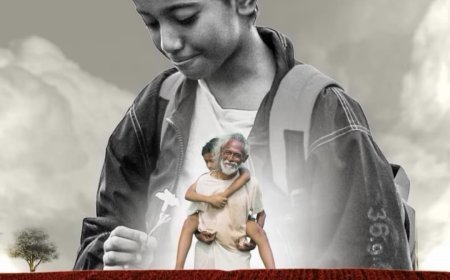

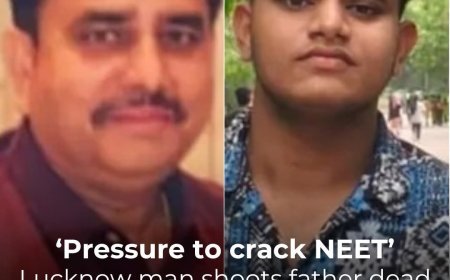

When a 65-year-old man and a 50-year-old woman embark on their householder journey — often for the first time — they are entering a role meant for their children’s generation. This reversal challenges not only the chronological logic of human development but also the spiritual and ethical blueprint of Hindu philosophy.

The Consequences of Delayed Grihastha

1. Biological Mismatch: The Grihastha stage is closely tied to procreation and raising the next generation. While not all marriages must result in children, the Shastric expectation includes the duty of preserving lineage, guiding progeny, and contributing to society. At 65 and 50, those natural windows have largely passed.

2. Derailment of Vanaprastha and Sannyasa: When one begins married life in later years, the opportunity for Vanaprastha — withdrawal from active household duties and movement towards spiritual contemplation — is lost. Consequently, Sannyasa, the highest goal of complete renunciation and search for Moksha (liberation), becomes a distant or even irrelevant pursuit.

3. Social Imbalance: Younger generations look to elders for wisdom, guidance, and a model of detachment. But when elders themselves indulge in late-life romanticism, extravagant marriages, or fresh worldly entanglements, it confuses the moral compass of society, especially in an age already strained by materialism and delayed responsibility.

4. Loss of Intergenerational Wisdom: The ashrama system was designed to transfer wisdom, wealth, and responsibilities progressively to the next generation. A 65-year-old beginning the Grihastha stage may instead cling to roles meant for the youth, depriving society of mentorship and experience where it’s most needed.

Why Is This Happening?

Modern Lifestyle Choices: The globalized world promotes careerism, personal ambition, and freedom of choice, often delaying marriage and family.

Fear of Loneliness: Emotional and social voids in late life push individuals to seek companionship through marriage rather than spiritual solace.

Consumer Culture Influence: Today’s culture glamorizes late-life indulgence, encouraging people to "reclaim their youth" rather than embrace their natural stage of life.

Reclaiming the Sanctity of Ashrama Dharma

Hinduism thrives not in rigid orthodoxy but in timeless wisdom adapted with responsibility. It is not about policing ages, but about recognizing the sacred rhythm of life as guided by the ashrama system. Let us not forget:

Brahmacharya is not just about celibacy; it’s about forming a disciplined, focused mind.

Grihastha is not just about marriage; it’s about duty, charity, and righteous living.

Vanaprastha is not about escapism; it’s about reflection and sharing wisdom.

Sannyasa is not about poverty; it’s about inner renunciation and divine union.

When these stages are honored in spirit and followed in essence, society functions in harmony — the young are empowered, the middle-aged are dutiful, and the elderly are revered sages.

Conclusion

When a society celebrates a 65-year-old entering marriage as an act of modern liberty rather than seeing it as a disruption of dharma, Hinduism itself stands at risk — not from external forces, but from within. The ashrama system is not a relic of the past, but a roadmap for inner and outer balance. Let us return to it with understanding, not rigidity, and with reverence, not rebellion.

Let Brahmacharya be the dawn, Grihastha the noonday sun, Vanaprastha the sunset, and Sannyasa the starlit sky of liberation. Misplace the sun, and we plunge into darkness.

Sanjay Pattnayak

Sundargarh