From Visionary Plan to Unplanned Sprawl: The Evolution of Bhubaneswar

Bhubaneswar, one of India's pioneering post-independence planned cities alongside Chandigarh and Gandhinagar, was designed with a humane and sustainable vision. Yet, decades later, its growth has veered sharply off course, driven by market forces that have prioritised profit over ecology and equity. What began as a thoughtful linear city concept has ballooned into unsustainable urban expansion, encroaching on farmland, forests, and natural drainage systems.

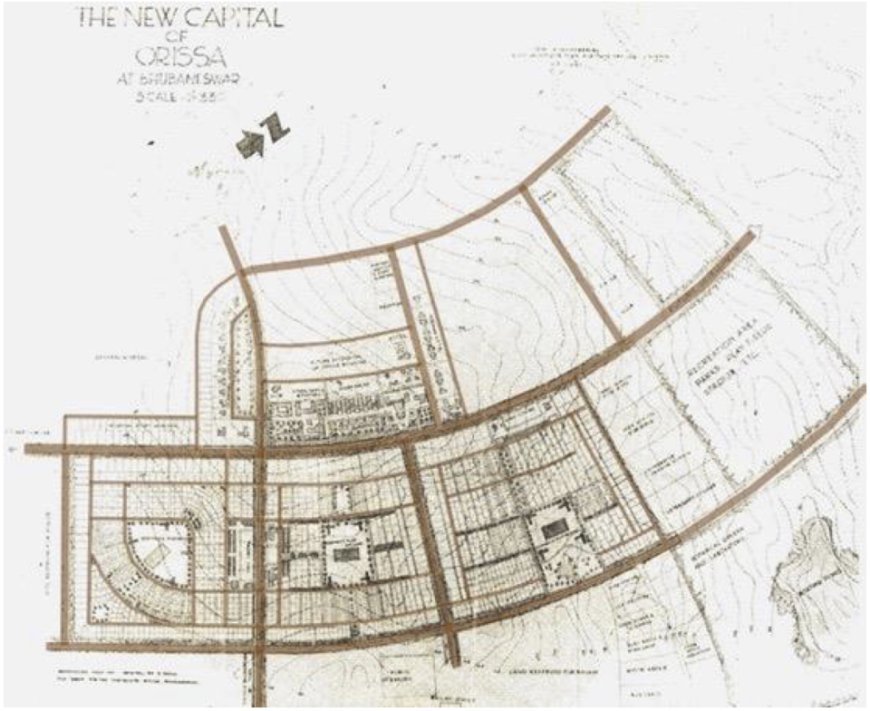

The city's master plan was crafted by Otto Koenigsberger, a German-Jewish architect who fled Nazi persecution and later became an Indian citizen.

Invited in 1948, Koenigsberger drew inspiration from neighbourhood units—self-contained clusters of about 150 acres, organised to capture cooling southern breezes, with homes featuring front gardens and rear courtyards. Each unit included walkable access to schools, shops, dispensaries, and parks, fostering community ties and civic responsibility while echoing rural life's healthier aspects.

This linear design allowed for modular expansion: additional units could attach to a central artery, supported by a hierarchy of roads prioritising pedestrians and cyclists over cars. Influenced by the Garden City Movement and his mentor Bruno Taut, Koenigsberger emphasised single-storey bungalows suited to Odisha's climate, promoting harmony with nature.

The plan partially aligned with Jawaharlal Nehru's 1948 foundation-stone vision of a city reducing rich-poor divides, but it introduced hierarchical grids segregating housing by government officials' ranks—a pattern echoing Chandigarh. Limited funds and Nehru's greater focus on northern projects inadvertently allowed Odisha leaders more autonomy, enabling some participatory elements in architecture and identity-building, distinct from the old temple town.

Initially limited to a few units for an administrative hub, the city grew modestly. Early residents enjoyed spacious bungalows with vegetable gardens, fruit trees, and open spaces where children played freely amid breezes. Social bonds transcended caste and religion, nurturing a sense of belonging.

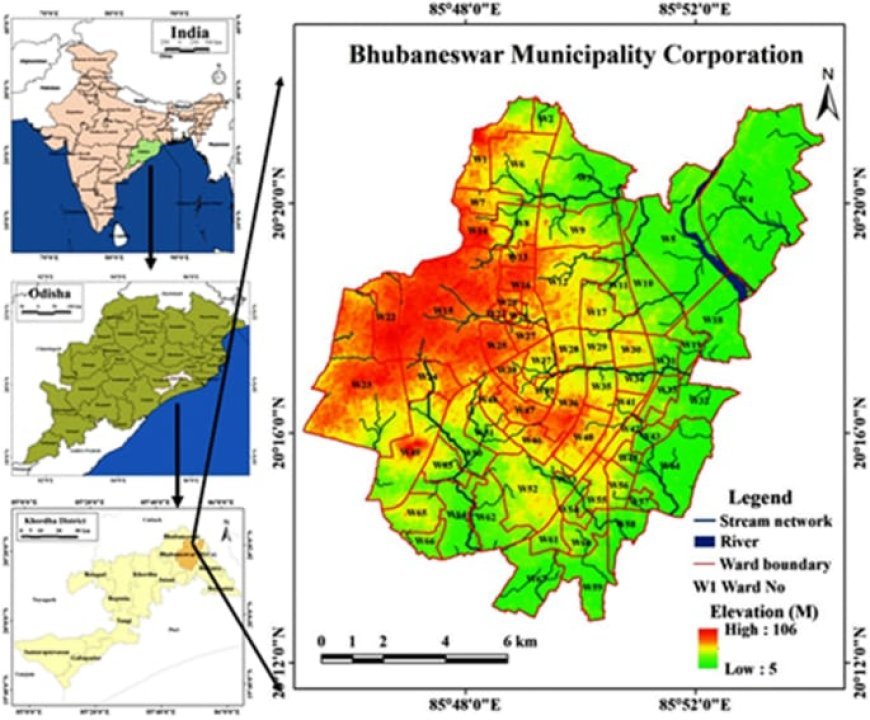

However, expansion soon outpaced the plan. Bhubaneswar's municipal area now spans around 186 square kilometres (with broader development zones larger), and its population has surged to over 1.3 million in the urban agglomeration as of recent estimates. Uncontrolled growth has merged it toward twin-city status with Cuttack, while sprawling outward in unplanned directions.

Real estate speculation has converted vast agricultural lands into high-end housing, ignoring natural terrain and drainage. Forests like Nandankanan and Khandagiri have shrunk, hills bisected by freeways, and mangroves degraded. This has intensified the urban heat island effect, with temperatures soaring and tree cover declining. The city is now car-dependent, plagued by congestion, inadequate public transport, and poor pedestrian infrastructure. Cyclones hit harder amid weakened ecosystems, and altered drainage raises flood risks.

Koenigsberger advocated public participation and publication of his plan for feedback, but it circulated only among officials—a missed opportunity for inclusive planning. Today's development often sidelines people's voices, favouring market-driven projects that exacerbate inequality and ecological harm.

Bhubaneswar's trajectory highlights broader lessons: master plans falter without integrating existing contexts (like the temple town), community involvement, and ecological safeguards. Top-down approaches yield to time and unchecked growth. For a sustainable future, the city must pivot toward nature-based planning, equitable access, and participatory processes—reviving the original spirit while adapting to modern realities.

As urban planner and activist PK Das reflects from personal memories and decades of experience, spaces profoundly shape lives, societies, and environments. Bhubaneswar could still reclaim a balanced path.

Sanjay Pattnayak

Sundargarh